Glimpses of Small Town India of Yore

I was ten when Daddy put me on a train to Ambala. Alone and unsupervised for the first time, feeling quite grown up, I hope I am hiding my fears. Daddy sent a telegram to his older brother, Har Narain saying, “Sunita is coming–please receive.” An immediate response comes back, “Who is Sunita?” I am better known by my informal name of Nanni or Nita.

Daddy’s two older brothers live in Ambala, where Daddy was born. I am going to spend the summer with my cousins. It is an eye-opener of a trip in countless ways. I am away from Mummy, Daddy, Sudhir, and baby Munna for the first time. No parental supervision!

Ambala differs vastly from metropolitan Delhi. Almost rural, although it has a thriving main street and a small cantonment. Summer flies buzz around incessantly, even in the hot, blinding sunlight. Some mornings, my cousin, Guddo, and I walk barefoot to a little pond, the Diggy, near the house. We watch ducks and ducklings paddling along in the murky, still waters. A few lotus flowers raise their brave heads between leafy pads. Squelching mud through our toes, we walk back home, dried muck crusted to our ankles. We took turns working the hand pump in the courtyard to wash our feet.

It is not a small house. Rooms line the open courtyard on three sides. A fairly large kitchen and pantry are on one side; an enclosing wall on the fourth provides privacy. A doorway leading to a narrow street behind. The hand pump, near the kitchen, is the sole water source for the entire house. I love working the pump and helping fill buckets to be carried to the kitchen or the bathroom. It gushes, sparkling spurts. One can sit cross-legged under it and enjoy the cool flow of water from head to toe. Somebody must vigorously handle it continuously. Guddo and I enjoy working with each other.

Every few days, Auntie sends me running to fetch something from the corner shop. The shop owner loves to practice his English with me. A few customers standing by are surprised I can converse in the language. “She is from Delhi,” explains the shop owner.

Guddo takes me to her school a few times. I am shocked by this inside view of a parochial girls’ school. Young girls my age are so serious. They talk in whispers and answer questions from teachers with eyes downcast. The school does not allow loud talk or giggling.

A teacher stopped Guddo and asked who I was. An unsmiling Guddo, eyes downcast, responds I am her cousin from Delhi. The teacher returns my direct gaze with a disapproving look at my bare head and bare legs. All the girls have their dupattas draped over their heads in modesty and respect, as do the teachers. No one is running around calling each other, even on the bare playground devoid of swings or slides. Good little girls with dupattas shuffling around. Scary, huh!

I mentioned this to Daddy on my return to Delhi. He smiled and told me that girls are expected to behave like young ladies. I look at Daddy with a frown and he smiles. “Not everyone is a wild little banshee like Sudhir and yourself.”

On one occasion, the principal of the school comes to visit. She is a leading figure in the Local Arya Samaj, responsible for raising funds and running the school, an older, sterner version of her students. But she walks and speaks with authority, a covered head and all. I see my cousin’s wife, Vinod, bring in some refreshments. Her head is bowed and covered. She greets the visitor with folded hands and swiftly departs. Because she doesn’t speak Punjabi, they don’t engage in small talk. Amazed, I looked at my uncle. He is busy listening to the principal. Guddo is also present–it is her school principal, after all. I am introduced as the niece from Delhi, my uncle’s youngest brother’s daughter. At the mention of Delhi, I recall feeling a sense of relief and freedom to do what I wished. I don’t have to tread on eggshells for fear of stern disapproval. My escape came by visiting Vinod, my friend. Whew!

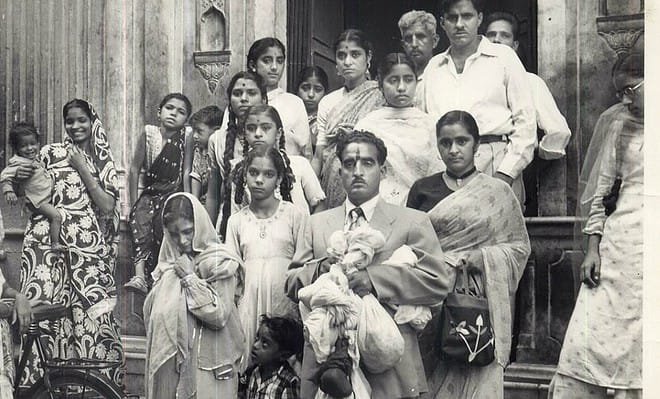

My cousin, Ved, his wife, Vinod, and their infant son live in the same family. Their marriage was an arranged affair. Despite exchanging photos, they had never met or seen each other until the wedding. The families had met and negotiated the marriage details. I’m not sure who introduced them. The young woman was visiting relatives in Delhi. Mummy and Daddy were asked to check out the family and the young woman.

We saw them, and Daddy had discussions with the father and other male members. Mummy and I sat in the small garden to talk to her. She scarcely spoke, replying to Mummy’s questions with nods or monosyllables. She is pretty, with a fair complexion. Passes muster on all points except the family is not Punjabi. They are Hindi-speaking from Moradabad.

Despite initial hesitations, the wedding finally happens. One of Vinod’s uncles raises loud, drunken objections at the wedding, causing quite a scene. With the wedding over, the camera captures a typical moment of the then-prevalent culture-a scared young woman leaving everything familiar to make a life with a stranger and his family.

Ved turns out to be a loving husband. As the daughter-in-law, Vinod joins the family and assumes responsibility for the kitchen. It sparkles under her care. She ensures delicious meals are served, and everyone sits down to dinner together. However, Vinod cannot stand the teasing of Ved’s younger brothers. They mock her pan-chewing habit and other small, unfamiliar ways. The continuous mocking is off-putting. She resents comparisons to the older daughter-in-law who lives elsewhere. Despite all this, Ved and she raise their son, who is a joy to the grandparents.

My Aunt has a sewing machine that treadles with one’s feet. The moment I see it, I want nothing more than to use it. Mummy‘s sewing machine is hand-operated. Only the left hand can guide the cloth under the presser-foot, not both. You need to crank the handle with your right hand. I pester my aunt to use this machine. She gives me some scraps of material to practice, but that is not enough. I beg her for proper material. She takes me shopping and buys me less than a yard of material. I loved the color–a dark carrot.

Excited, I cut off a strip and fashioned it into a waist belt. So far, so good. I hem the remaining material on three edges. It’s challenging to try matching the rhythm of my hands with the tread. The threaded needle doesn’t wait for me to straighten the edge. As the machine produces neat stitches, I cannot get them in line. The stitches are wavy at best, zigging and zagging all over the hem and sometimes slipping off. The hem slips out from under the pressor-foot, and partially unfolds. Constant shifting causes a messy disorder. I end up with crooked lines running onto each other. No matter–the hem is done.

Afterwards, I used a needle and thread to gather the fourth side and position the gathers in the middle of the belt. To align the gathers and belt under the needle is trickier than hemming. I go back and forth in crooked lines. Ultimately, I have a little apron to tie around my waist, an untidy mess of kinky, chaotic stitches and seams. But my aunt thinks the world of it. She takes it around the neighborhood, showing my handiwork to all her friends, taking pride in my independent accomplishment. Old-fashioned sewing machines with treadles hold a special joy for me.

I love our summer sleeping arrangements. The rooftop of the house is a large terrace. And like in Delhi, we slept on cots, under the stars. I remember one night waking up to some commotion with my uncle scolding two of my cousins. They had tried to sneak up to their cots around three in the morning. The boys were gallivanting around town with their buddies, and they lost track of time. And that was not the end. My cousins avoided my aunt’s mutterings for most of the next day. But she corners them and hears their stuttering excuses. “You braying asses,” is my aunt’s verdict, delivered in a loud, angry yell. Her “you don’t fool me” stance and tongue-lashing keep her boys in line and improve my phraseology.

Har Narain is an avid bridge player par excellence. He enjoys the game with his colleagues at the Officers’ club. My aunt has always been prone to illness, and her loving husband tends to her needs most of the time, except some evenings. Her bitterest complaint is that he hurries through attending to her to play bridge without a guilty conscience.

Then there is the Jain Soda Factory. It is always crowded and a favorite haunt of my cousins. They mostly serve cold drinks, snacks, and bottled sodas in a gazillion flavors. The bottles themselves are captivating. These do not have metal tops. The stoppers are a round glass marble halfway down the neck of the bottle. Watching the attendant push the marble down with a bang without shattering the glass is fascinating. They pour the fizzing soda into a tumbler with pizazz!

My other uncle, Sham Narain and his family live in a larger two-storied house around the corner. I still remember the second floor. It’s a vast room with many windows and doors leading out to a narrow balcony running along the front of the house. I keep staring at the floor of this room which isn’t cement. It is more like dried mud – strange!

My cousin, Bholla, keeps up a lively chatter. She has an amusing way of talking and mimicking people. The following day, Bholla asks me if I was a good helper. Of course, I am. “Let’s go,” she says, running upstairs with me close behind her. Bholla hands me a broom, and we sweep the room between us. Squatting on the floor, we waddle like ducks wielding the brooms. When we are done, I point to the floor and ask her why it is coated in mud. Bholla explains the clay keeps the room cool. The searing hot summer sun and hot winds do not heat it. When the doors and windows open after sunset, the room is cool and pleasant to sit and sleep in.

Yet, there is still unfinished work on the floor. Bholla makes a gruel-like thick mixture of clay, water, and finely chopped straw. On our hands and knees, we pour and spread it across the floor section by section, moving backward as we level and smooth the surface. When we reach the top of the stairs, we stand on stiff knees and admire our handiwork—clay cakes our feet, hands, and hair. We clean up with rags and make our way downstairs. It has taken us the better part of the day to complete this task. We must wait until tomorrow for it to dry. The room smells good–a mix of wet clay (like earth after a rain) and a hint of pungent straw.

Decades later, I find myself in a candle store in Chicago. The aroma of some smoldering pellets transports me to that long ago day. Images of Bholla and me laving the floor with clay and straw leaves me wistful for a simpler, innocent time.