Mathura and the Taj

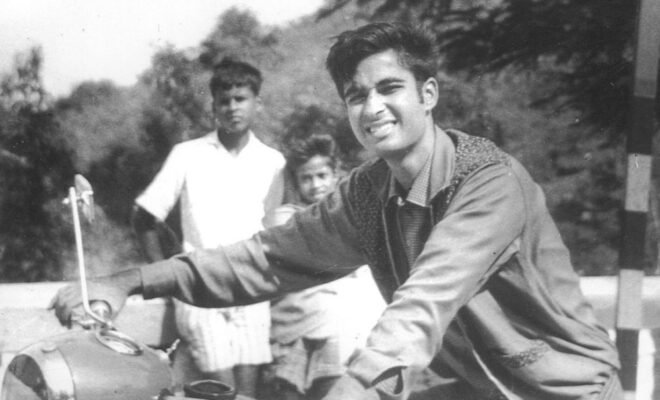

Visiting Mathura is another memorable trip with three siblings and our parents. I am ten, Sudhir is two years younger, and Munna is a toddler. The year-end exams are over, and the winter vacation has begun. Daddy is to leave on one of his trips to the rural countryside. He had run into an old military friend a few days earlier, a colonel in the armed forces. Upon learning that Daddy would tour in his vicinity, he invited our family to visit him in Mathura and stay at the military guest house. It is an old bungalow, still maintained in the colonial British style.

The cook-cum-caretaker presents meals that seem fabulous to Sudhir and me. Eggs and hot buttered toast follow a breakfast of cornflakes and milk! Wow! A double-deal! Our daily routine at home is to gulp a tall glass of warm, sweet milk and hurry to school. On weekends, Mummy never gives us a choice. We have either eggs or cornflakes. Occasionally, we have Indian-style parathas with fresh butter and jam. But now Mummy is intent on civilizing us by dressing for breakfast. We enjoy play-acting refined behavior, eyeing each other across the table. Each time the cook comes around, we exchange looks with hands in our laps—no reaching or grabbing in his presence. We are out to impress the cook.

Lunch is another novel experience. At home, with Daddy at the clinic, lunches are uncomplicated, devoured in the kitchen, and served from the pot. We are not used to sitting at a table with only Mummy. A snow-white tablecloth and folded napkins are included! The cook places a salad on the table and pours water into glasses. Our eyes pop right out of our heads as he enters again, bearing an enormous platter.

It is steaming and piled high with fragrant fluffed rice nestling in curried meat and vegetables. He brings it around, and we wonder if Daddy will have the leftovers at dinner. We can’t do justice to this meal fit for a king, eating only a fraction. A delightful caramel custard is next. Finishing most of these poses no problem. Daddy returns early in the evening, and we visit the Colonel and his family. We never discover if he had the leftovers from that fantastic lunch.

The Colonel’s residence is a large gated bungalow with lush greenery and flowering shrubs lining the driveway and the entrance. I recall little about the family and remember his wife and mother, but no children. She is visiting her son and profoundly desires to see all the temples in Mathura and nearby Brindavan. The weekend is coming, and the Colonel invites us to join him and his mother for a few days of sightseeing.

Temples fill Mathura and Brindavan, solely dedicated to the early years of Lord Krishna. We visit most of them. Growing up filled with tales and legends of Lord Krishna’s childhood, we now find ourselves in the very place where it all happened millennia ago. The tree under which the miracle of raas occurred is still spreading its shade. I can visualize Krishna cloning himself so that each gopi (milkmaid) can dance with him. I can hear the haunting notes of his flute. The river banks at which the gopis bathed and fetched water stand at its edges. I try to imagine the pranks of the young Krishna and his playmates. The Colonel’s mother and Mummy listen to the guide with rapt reverence.

The older woman fascinates me. She speaks Hindi with a charming Bengali accent (rounding all the vowels) and refers to Lord Krishna as Thakurji (lord and master). She has long, thick, snowy hair, which she wears in a loose knot at the nape. Now and then, the twist gives, and the gathered strand slithers down her back. She shakes her mane, gathers it in both hands, and binds it up. I monitor that nub and observe the twisted tresses slip gradually and come unbound. A vigorous nod of the head helps the knot loosen up, and there it goes, sliding down her backside.

The guide is pointing to the middle of the river, Jamuna. He recounts the smuggling of baby Krishna out of prison right after his birth. While crossing the surging waters on a stormy night, Vasudev places the newborn in a basket carried high over his head. As the rains pour, Nagaraj, the King Cobra God, uncoils and emerges from the raging waters. Spreading his majestic hood over the infant, he shields him from the rain. The breath from the poisonous fangs envelops the infant and gives his skin the legendary blue hue.

I look back at the older lady. Gripping her hair in both hands above her face, she twists it into a firm knot, like Nagaraj protecting the Thakurji babe. Mummy and she compare notes. They hold the same religious beliefs and follow the same daily rituals. I am attentive to their conversation and their laughter. I love the special bond pulling them together despite their age difference.

Two temples stand out in memory. Monkeys abound everywhere in Mathura. We delight in their antics and throw peanuts at them from a safe distance. Crowds of people hold no fear for them. Some approach us with curious expressions. “Do you have a treat for me?” At one temple, I walk down a path with my icy hands buried deep in the pockets of my red winter coat. A duo of long-tailed simians, taller than the two-year-old Munna, sprint up to me and lift themselves upright, their paws on my arms. My screaming does not daunt them until the guide runs up and swats them away. I stayed near the group after that.

A temple by a pond has many giant turtles. People in Mathura consider them sacred, like all living creatures. Visiting devotees and tourists feed them. Sudhir and I clamor to Daddy for coins to feed our new pals and watch how they snap up these treats in mid-air, extending their necks in all directions. The guide warns us not to get too near them. They attack with a ferocious bite. The afternoon passes by, feeding and watching our new amphibian friends.

One morning, Daddy took Sudhir and me to work with him. The community is rural, with a nearby school near the guest house. The students give curious stares as the medical entourage drives up and begins set-up. We spend our time befriending the children with our wrapped candy. Dad has to go somewhere else later. He asked if we can go back home on our own. Although the bungalow sits on a side lane, the road passes through a few neighborhoods. There’s no requirement to cross a road in the nearby commercial area. You don’t have to remember or get lost on any turns.

It is a slow, carefree amble back, where we walked a bit and then paused as something caught our eye. We are used to walking down streets in our neighborhood. Here, we are looking around and taking in unfamiliar sights and sounds. As we go through the bustling area, we encounter a blind man tapping his cane on the sidewalk. He is saying something. We listened to his request for help crossing the street. Not true bona fide scouts, we are familiar with their daily act of kindness routine. Sudhir grabs the walking stick and leads the man across. I stumble forward, trying to get a slight hold on the cane. My brother keeps shoving me away. He grabbed it first. It’s his show, his good deed today, and he is not ready to share bragging rights. The task is completed and we return to the other side.

I argue with him, still simmering for being denied a role in this noble act. We continue arguing about each other’s meanness. Words heat to an elbowing match. Sudhir pushes me hard, which escalates into hitting each other. Soon, we were in a brawl, yelling, shouting, and pulling each other’s hair. A couple of “concerned citizens” separate the two of us. And a scolding ensues for our disgraceful public behavior. One person orders us to return home after discovering we are siblings. We slink back to the bungalow.

Mummy looks at our disheveled appearances; she knows we have fought. All her inquiries are useless, with the strangers’ scolding ringing in our ears. We dare not talk of the blind man and our righteous deed for fear of all the disgraceful happenings spilling out. Not only did we have a physical altercation in public, but we also crossed a traffic-ridden road twice. A huge no-no! Later the same evening, Daddy tries to pry the story from both, but our stubbornness comes in handy. We do not surrender to his tactics, staying faithful to each other.

The events of the previous day slip from our minds by morning. We rise early and depart for Agra. It is a brief trip to historic sites, including the iconic Taj Mahal. The starting point is the Red Fort, resembling the one in Delhi. A sprawling grand Mughal structure architected and built with Rajasthan’s red sandstone. It comprises an impressive diwan-aam (public meeting hall) and a majestic ornate diwan-khas (hall of particular audience). Scattered around are small palaces for the favorite queens. The section where Aurangzeb imprisoned his father, Emperor Shah Jehan (the fifth Mughal emperor), is especially poignant. This Mughal built the Taj to immortalize his beloved and spent his last years gazing at it with fading eyes. History remembers Aurangzeb more for his cruelty and fanaticism than anything else.

The Taj is our next stop. While exploring, we hear about the thousands of expert artisans and how long it took to construct it. Brutality runs through history. The emperor maimed the craftsmen after its construction, a well-known historical fact. The Taj has to be unique. We hear the words again, like new. We admire the multi-shaded leaves and flowered vines etched and inlaid into the white marble. Brush our fingers over the exquisite work to feel the smooth in-lay seams. The unparalleled talent of the artisans and their fate registers again. Sudhir and I peek at each other through delicate, filigreed stone screens and walls. Daddy walks around, studying the intricate Arabic/Persian script engraved high upon the arched doorways.

We revisit the Taj at night, bathed in the full moon’s light. Daddy has planned it well. It is more than an unforgettable sight. Against a vaporous sky, the pearl-gray marble cupola looms luminous from a distance. Holding Daddy’s hand, we enter the high-arched entrance and walk along fountained paths. The translucent Taj radiates an ethereal beauty in the cold moonlight. Precious stones and gemstones ensnared in the glimmering glint of the granite, prick like myriad stars. As we near it, the gems embedded in the tomb’s magnificent dome sparkle in the night sky’s reflected light. It is an awe-inspiring panorama. In my thoughts, I understand why it’s one of the seven wonders of the world. In some elusive measure, I also grasp how the cruel act of the emperor was justified in his smitten grieving soul.

Once more, the guide is rambling. The shining dome and the higher reaches of the mausoleum had escaped vandalism by British soldiers. Precious gems still encrust the trailing tracery of the etched vines. He previously showed the hollows in the patterns on the lower walls, showing the missing gems.

With Munna’s hand in mine, I stroll around the magnificent structure, ensuring she sees the twinkling stars in the ghostly gray marble. I want her to remember this. Years later, Mummy, Munna, and Juji visit our cousin Pran and his family in Agra. They see the Taj and the rest of the historic sights. But they do not experience the Taj on a moonlit night or listen to Daddy’s gentle voice reciting the ancient engraved scripts.