Growing Up – The Delhi Years

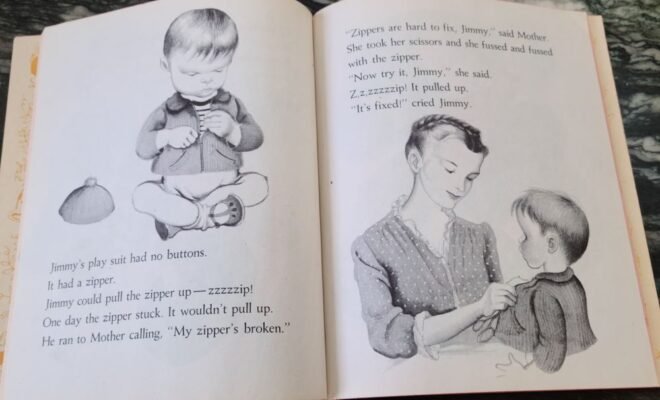

“Yes, Daddy, yes! That’s the book the teacher read in class.” Daddy is turning pages of a children’s book entitled Fix it, Please. We are in a children’s bookstore. My teacher, Miss Beri, had read that book to the class this morning at school. She displayed it to the kids so they could see the pictures.

Earlier this evening, the picture book dominated my response to Daddy’s “How was school today?” In the blink of an eye, my little brother Sudhir, Daddy, and me are all in the bookstore. I remember seeing some books on the school shelf that I recognized. I point to the Fix It, Please one for Daddy. With each turn of the page, a young girl and boy run into problems and run to their parents for help. I spent the entire day trying to figure out how their mom fixed a stuck zipper using only a pair of scissors. Even after several decades, I ponder about this.

I started school when I was four years old, with only a smattering of English. From kindergarten, our teachers encourage us to speak in English. The teachers speak English, and I somewhat follow what they say. At home, my stories of school fascinate Sudhir. His eyes widened when I described any interactions with Miss Beri. She will not let me go to the bathroom until I request permission via a complete English sentence. I go up to her and ask, “Miss, bathroom?” Her firm response is, “Say a complete sentence.” I’m hopping from one leg to the other. She sees the urgency, scolds me, and sends me rushing off.

Sudhir listens to the songs we sing and the games we play. Head cocked to one side, his curious questions come tumbling out. The picture books hold a particular fascination. He learns some songs from me. I cannot recall any since neither of us understood most of the words. Sudhir and I play games, changing rules as we please. He wants to go to school with me, and I’m eager to take him.

I picture this rosy-cheeked little toddler holding my hand, clinging to me at school. The day arrives, and we’re both dropped off at school. As I entered the classroom, Sudhir froze, let go of my hand, and refused to enter. He waits outside the door, trying to look as nonchalant as only a three-year-old can. The class files out for outdoor games. He follows us at a distance, refusing to come any closer. Miss Beri asked who the little boy was, and I claimed him. Miss Beri throws me a reproachful look. She approaches him, holding a friendly hand and saying soothing words. Seeing Miss Beri nearing him, the terrified Sudhir heard none of her kind words. His face crumbles, and he breaks into a bawling mass of tears. I die of embarrassment!

In another two years, Sudhir is ready for kindergarten himself. Mummy and Daddy take him to his first school day. They know the principal, Mrs. Gibba, and she guides them to Sudhir’s classroom. Intimidated by the sight of a bunch of strange children, he refuses to let go of Mummy’s hand. All the coaxing, the tempting display of new toys and picture books, doesn’t matter. He hasn’t forgotten the trauma of his earlier school experience. The four of them return to the principal’s office. Mrs. Gibba tries to befriend Sudhir and beguile him with some of her teaching toys. With an eye on Mummy and Daddy, Sudhir warms up to Mrs. Gibba. Together, they turn picture book pages, and Mrs. Gibba narrates the story. Sudhir laughs at a funny part and comments. Mummy and Daddy take this opportunity to sneak out of the office. Sudhir looks up, sees them gone, and runs after them. The principal tightens a comforting arm around his shoulders. But with one wrench, he frees himself and catches up with Mummy and Daddy. The trio returns to the office, and they apologize for Sudhir’s behavior. Daddy tries sweet-talking him into returning to class. He hangs on to Mummy’s kameez so tight it rips in the scuffle. Back home, no one mentions school to Sudhir over the next several days.

Every other evening, Daddy comes home with a gift for Sudhir. A cricket bat and ball set one day, wickets and knee pads the next, colored marbles, a picture storybook. The message changes with each gift. Sometimes, the gift is from the principal or the teacher. Both are looking forward to seeing him again. No one mentions anything about school. It’s as if no one remembers Sudhir’s behavior. Pretty soon, my eager brother is clamoring to go to school again!

This incident remains in people’s memories. A smiling Mummy recalls the events of that day to visiting friends and relatives. They listen, laugh, and nod in approval of Sudhir’s behavior.

Growing up in Delhi, the contrast between summers and winters is stark. Soft winter sunshine is perfect for basking all day. Daddy spends entire weekends outside on the verandah. Mummy serves lunch out here. This is also the time to be out and about. Summers are searing hot and the landscape parched. Sand-laden winds come howling from the Thar Desert, ensuring a constant grit in one’s mouth.

The Mogul Gardens (Presidential Gardens) are in full bloom and open to the public. Walking paths take us around myriads of ponds in a floral paradise. Gorgeous colors in patterned arrays, encircle fountains, and pools. We spend half a day walking around the gardens, oohing and aahing. I recall walking ahead and hearing a commotion behind me at one juncture. Turning, I see Sudhir has slipped and fallen into an adjoining pool. Mummy is fishing out a thrashing five-year-old. It’ss cold, and he’s hurriedly dried and draped in Mummy’s shawl. Daddy’s jacket is handy, and Sudhir is clasping it around him. A small crowd, relieved to see Sudhir safe, clapped and laughed. Someone says, “A dip in the holy Ganges makes one blessed, not these tiny pools.” Hair still dripping, teeth chattering, Sudhir musters a brave grin.

Winters turn into springtime, and it is Holi, the festival of colors–a celebration of an early harvest. We have our spring-loaded brass water guns tested and ready for Holi. Hordes make their way to the vast forests behind Birla Temple. Several square miles of preserve teem with Tesu trees in full bloom with flowers (Flame of the Forest). Soak the orange-burgundy flowers in buckets of water overnight. These render a reddish-orange color to the water. Traditional Holi means spraying friends and family with this fragrant-colored water. Gulal (red-colored powder) is also used to smear each other and toss clouds amidst shouts of “Holi hai”-it’s Holi. Sudhir and I revel in Holi and its hues. The cheap store-bought colored powder dyed in every hue (fake Gulal), takes a few showers with vigorous scrubbing to remove stains from the face, arms, and legs.

Close on Holi’s heels, follow scorching hot winds. The “loo” blows across central India straight from the Thar desert. Roasting, sand-laden dust storms sweep across the cracked, arid landscape. Daddy says this makes people hardy. I do not want to be that tough. Sudhir suffers from nose-bleeds playing marbles in this blistering heat. Mummy makes him lie flat with his head hanging back off the edge of the bed. Dousing cold water on his head stems the bleeding after a while.

Delhi summers are only good for mangoes, watermelons, and Mummy’s sardai. Every morning, we wake to the sounds of Mummy churning fresh butter. But summer mornings carry another rhythm as well. A large stone mortar holds a mixture of soaked almonds, poppy seeds, and aromatic spices. Ground to a smooth paste, it is watered down with milk, sugar, and ice. The sweet cooling concoction is part of our daily breakfast. And oh! There is no school for a full two months.

Summer progresses. Dark thunderous clouds echo and peek above the horizon as the heat becomes unbearable. In the middle of the night, these roll across the skies. The welcome monsoons break with slanting sheets of water. Streets, trees, and houses get a thorough rinsing and more. Sudhir and I chase each other across the wet, slippery verandah in the pouring rain. The last Mogul Emperor, a poet, had a special pavilion built to enjoy the monsoon season. Fellow poets gather, recite their poetry, and feast on mangoes as the rain drums a steady tattoo.

Divali, the festival of lights, is a wondrous time. Daddy takes us shopping for diyas, tiny earthen oil lamps, and fireworks. We love walking through the crowded bazaar. The hustle and bustle of brisk business leaves us spellbound. Decorated storefronts and impromptu fireworks stands hold a unique charm. Mithai shops are where Indian sweets are found and they teem with mouthwatering silvered desserts.

Back home, we soak the diyas in water and then line them upside down in the sun. By evening, the diyas are dry. We position them in rows along sills, balconies, and any place that will hold a diya. Mummy follows us, placing hand-rolled cotton wicks in each diya. Daddy pours a little mustard oil into each as well. Our baby sister, Munna, toddles along, prattling and begging to place wicks herself. Mummy sets up a little temple in the living room. Goddess Laxmi, adorned with fragrant flowers, diyas, and mithai, presides.

As evening fades, we light the diyas. After Laxmi Puja, we are on the verandah, ready for fireworks. A Sulfur smell permeates the air as clusters of tiny bombs explode in a series of rat-a-tats. Not once, but in rapid succession. Our neighbors’ boys have taken the lead in deafening noise and fireworks. Daddy, a stickler for rules and safety, gives Sudhir and me a silent signal. We understand there must be none of that. We take turns lighting sparklers and swishing these around in circles. Lighting flowerpots have a thrill of its own. We watch the narrow stream of fire shoot straight up to explode into a canopy of colored sparks. Rockets fired straight up into the sky end with a loud bang amidst a delightful explosion of stars. We look around at other buildings down the street and beyond. Candles and diyas outline windowsills and parapet walls—colorful fireworks and dense, acrid smoke cloud the air. Delhi is a sparkling, twinkling fairyland.

The following day, shredded paper and stubs litter the verandah. Sudhir and I have our work cut out for us. Mummy cannot sweep the verandah; we will not let her. We will also not be hurried. Checking each stub to see if it has exploded takes time. We gather the unexploded ones and put these aside in a small, pitiful pile. When done, we take our unexploded pile of treasures, place it in a metal bucket, and drop a wad of lighted paper. We revel in the few reluctant bangs we hear. Another Divali is now declared over.

Sudhir and I don’t know Daddy has a gun. We see it when a friend wants to shoot pigeons. Sudhir and I, wide-eyed at the sight of it, look at each other. Is it real or a pretend one? Daddy and his friend go to the roof; we cannot accompany them. They come down a little later with a couple of pigeons wrapped in bloodied newspapers. The friend likes the gun, and a barter is complete.

A glimpse of the lifeless pigeons scares us out of our wits. Mummy informs us the gun is being swapped for a machine for the two of us. Wow! What kind of a machine? A sewing machine? I look at Sudhir-he frowns and mouths a silent “no.”

It turns out to be a fretwork machine operated via a foot treadle. The narrow blade moves up and down, cutting out patterns traced on thin plywood sheets. We enjoy making small picture frames by tracing patterns on plywood. Love it for a while, and then it gets boring.

Daddy’s transfer to Bangalore brings an end to fretworking and much else. The move from Delhi to Bangalore opens up new vistas for all of us.