The Fish Tank

Brennan’s Jetta puttered to a stop when the railroad crossing arms lowered. The crossways fell like a protective parent’s arms to their child. Cold air blasted through the vents, and the wipers scraped jagged strips of ice across the windshield. Raindrops froze in streaks. He blew into his folded hands. Beside him was a thin satchel and plastic bag with the remains of his lunch.

The train rattled by with its rhythmic passage-clack-clack-clack-clack as it passed over the crossing. Its direction led Brennan’s gaze to the house on the opposite side of the street. A wooden fence separated the residences from the busy street. A violet light caught his eyes from an upstairs bedroom in one home. He saw a young boy, around eleven or twelve, as he stood by a fish tank and sprinkled food into the water. Brennan couldn’t see the fish’s size or colors but imagined them as bright as Jolly Rancher Tropical candy. After the endless line of railroad cars, the red lights and bells stopped. The boy looked up, startled, in Brennan’s direction. Could the boy have seen him? How could he have from the window? Glare from rain, fallen sun, and headlights obscured their potential connection. He disappeared into the shadows of his room.

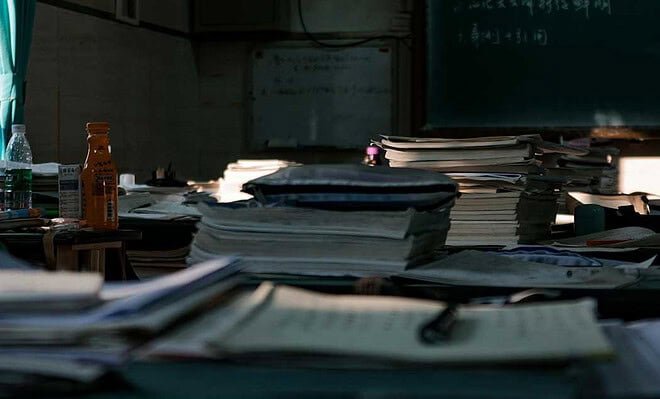

The crossroad arms once again halted Brennan’s commute the next day and the day after. Red flashing lights reflected onto the boy’s bedroom window, and the fish swam under the lavender light. This time, the room illuminated slate-blue walls and chocolate-stained bookshelves. A woman, presumably his mother, appeared in the doorway and spoke to him.

Each day, in his beige cubicle, Brennan watched the clock on his computer until the minutes mounted to 4:48. If he left, he would reach the train tracks by his home and catch a glimpse of the boy who raised the fish by the windowsill. If he met the crossing arms as they descended in their slow halt, he took it as a sign the universe told him, Stop. Don’t go. Witness this. Even behind several stopped cars, he saw movement, and believed the boy was tending to the fish on the sill.

Days and months passed. The snow melted, and the sun warmed. The woman tended to a barbeque in the backyard. A man often joined them in the early evening. The top of the boy’s dark head glided around the driveway. Through the fence’s wooden slats, a hockey stick scraped the driveway. A small caramel-colored dog ran by the boy, its tail wagged like a propeller. Another evening, the boy was atop the jungle gym and swung his feet. His gaze was distant, withdrawn, as if he was regarding life beyond the over-developed horizon.

The summer days ended with Brennan finishing his commute along the thoroughfare parallel to the house. The fish continued to live on the sill, and the purple light was their hope in the twilight. Sometimes, the boy fed them. At times, he was close to the home with the dog, in the driveway, or mowing the lawn. One day, he got into the passenger seat of a car. He’d grown taller and had to bend his long body to get in.

As time passed with the seasons, the boy was frequently absent, and the residence was increasingly dark. The winter days approached. Weeks passed, and the first snow left a thin layer, though patches of grass remained. The woman fed the fish.

In darkness, one night, it was hard to tell if any life was left in the house. The thought would not leave Brennan. The boy’s absence haunted him in those few minutes of early evening and persisted through the night and in his dreams. Work was nonexistent. With darting eyes, he mechanically checked the time on the computer screen. He left work at 4:48. The cross arms lowered, and the house was lifeless. Brennan crossed the tracks but, on impulse, circled back to the boy’s neighborhood and parked when he determined which one it was. He paused, drummed his fingers on the steering wheel, then walked to the door. The porch light illuminated as the woman’s face emerged from a nearby window. She opened the door, crossed her arms, and waited for him to speak.

“I’ve driven by your house every day. Over there on the main road,” he began. His nerves for bravery moments ago turned to severe doubt and crumbled confidence.

The woman raised her eyebrows and stuck her tongue under her lip like she was trying to hold back words she wanted to spit.

“I’ve seen the boy. Your son?” Brennan gestured with his hand to show what might be obvious.

“Who are you? What do you want?” She asked, shifted her stance, and re-folded her arms.

“Is he alright? I haven’t seen him in a while.” Brennan’s heart fluttered like the tiny finches he had kept as a child.

“He’s gone to college. His father left in case you’re curious about that as well.” She scratched the side of her neck and left red streaks. Her voice softened. “How do you know my son?”

“I don’t. I’ve driven that road back there for years.” Brennan pointed to the boulevard.

The woman waited. Brennan took too long to respond. She shook her head. “I can’t help you. Sorry, I need to go.” She closed the door.

“But the fish–” He wanted to know.