Beloved Brother Gone-Part 2

- Beloved Brother Gone-Part 1

- Beloved Brother Gone-Part 2

The visit to Ottawa ended. Nothing had been resolved. It was clear Sudhir needed to continue under supervised care, and he was sick of it. As he put it, I am wasting here.

Returning to the airport, I stopped to say goodbye. I walked upstairs to check out his room. We uttered words of getting together again soon, but made no concrete plans and set no date. Huge raindrops signaled the last of the hugs and kisses as Sudhir and I said goodbye. His hair and beard felt soft. He shampooed with the fresh bottle we had recently bought together at the Giant Tiger. The rain was coming down a little heavier. I gave him one last kiss and hug and ran to the car. I promise I will call you every week; I told him. Drive carefully, he said as I waved from the car.

In the rearview mirror, I saw him standing on the steps of St. Joseph’s facility that last morning in May. He watched me go down the sloped driveway. As I rounded the curve, I saw him turn back and go up the steps, shoulders sagging, suddenly bent forward like an old man.

As I sat in the somber room, listening to the chanting of the priest reciting Sudhir’s death rites, my thoughts continued to wander off. A few weeks earlier, I had been checking out groceries at the Indian store. I noticed a basket full of colorful, glittering rakhis. Sensing my eagerness, the store owner, saw me smiling. He explained to a couple of curious customers. It’s a celebration of sibling relationships, of loving bonds between brothers and sisters. The owner informed me Rakhi was August second this year, an annual celebration. Elated, I walked out of the store, making extraordinary plans for Rakhi.

I could not recall the last time we had tied rakhis on Sudhir’s wrist and applied the red tilak to his forehead with a scattering of rice and saffron. Prayers are offered for a long and happy life. This year promised to be unique. It would be an exceptional occasion!

As I am jolted back to the rituals, I realize today is Rakhi, August second. In my realization, I look around the little circle. The priest is chanting a very different set of prayers. The priest must know what day it is, and I’m grateful he does not mention it. Mummy would have broken down. As it is, she seeks solace in reading after reading of the sacred scriptures.

Mummy tearfully kissed the draped pine box. Fred walked up to it. Rapped his knuckles on the pine box, he bid a silent goodbye. We leave Sudhir covered with the flowers he had so dearly loved. The flickering oil lamp glows to light his journey beyond till we meet again, little brother, till we meet again!

Leaving the funeral home, Munna mentions she had taken Sudhir for a long drive a week before his passing. She recounts how sullen he was, as if he were some place else. He only perked up when they drove past the Salvation Army facility where he lived for several months with his friends. He had been happy there. But with no medication and a careless diet, it played havoc on his diabetic condition.

Years later, other scenes kept rolling in my head. Sudhir must have eagerly awaited news of a glimmer of hope. A despairing yearning, we would be with him, help him, shore him up every step to recovery.

The new medication successfully cleared the fog from his mind. He stood alone, surveying the shattered ruins of his life. The drug was not adequately monitored for its effects and no therapy sessions to glean the clarity of his mind.

There is no need to involve or inform the family about the new drugs, and no appraisal of his progress and needs. The doctors made irregular weekly visits, occasionally skipping a week or two. We could meet with them, if we wanted to, and if they were available. He shared his thoughts with no one and only asked for help to move out of the facility. We promised to get him out of there once the doctors approved it. He needed to regain his strength. A few futile attempts were made on his own. The appointments and follow up with other doctors on weakened legs did not benefit him.

Unable to find the right words, he could not express the indignity he felt being confined here. Stripped of all sense of being, his disability payments and all other sources of meager income garnered. His independence and self-worth did not matter to anyone. The staff, for all the sham of caring, treated him as a minimal vestige of useless existence. I am deteriorating, he said during our phone calls and in person on my visit. He hated it with desperation. Moving out would have been an assertion of his returning capabilities, his self-worth. We feared he would stop taking his medication and slip back into the darkness he was coming out of.

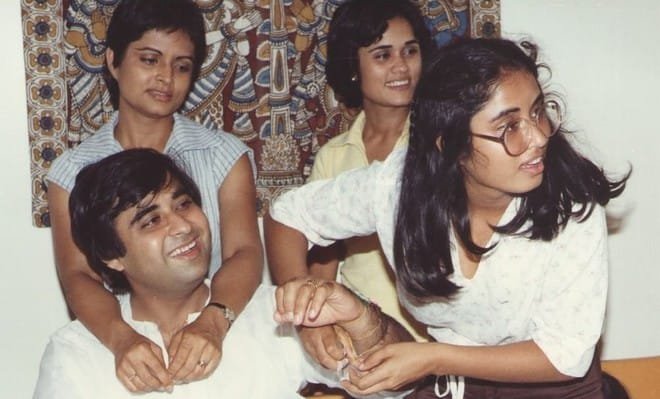

My thoughts traveled back further into our childhood. I was searching for symptoms or signs of the impending sickness. Upon Sudhir’s return from Canada to India, Daddy asked if we had noticed any changes in him. It was a brief trip after being gone four years. Per the Indian tradition, we had lined up a potential bride for him. They met each other and were captivated instantly. It was love at first sight! Sudhir had returned to Canada as a married man. Once his wife, Savita’s visa was processed, she followed him to Canada. Sudhir flew to Paris to get her. They had a delayed honeymoon, traveling all over Europe. And the answer to Daddy’s question, No, we had not.

But something struck me. We had visited the piece of real estate Mummy and Daddy had bought at an auction in Indira Nagar. Sudhir was all excited about it. Mummy proudly told us how once Daddy started bidding, she continued. Her heart was set on the corner lot. She kept raising the bid until she had secured it.

Sudhir asked Mummy what kind of house she would like to build. They got into a discussion as she described her dream house. Sudhir grabbed a paper and pencil, and together, they laid out a detailed plan for a home. It seemed like an exercise in futility. But Daddy said no, Sudhir was humoring Mummy after being away for four long years. He knew he would be returning to Canada within ten days.

I thought about when we lived in Delhi. We were very young. A Sunday trip to India Gate was always exciting. Sudhir and I chugged up and down the long, narrow waterways, paralleling Rajpath in individual paddle boats, the grand boulevard from India Gate to the President’s residence atop Raisina Hill. This trip, Daddy rented a regular boat with oars to introduce Sudhir and me to the fine art of rowing. We spent the entire morning on the boat as Daddy showed us how to grip and wield the oars properly. It was a fun morning, and Sudhir and I enjoyed taking turns at rowing.

By early afternoon, Mummy said it was time to head back home. Sudhir wanted to stay. Daddy promised to take us the following weekend, but Sudhir would not budge. We all got in the car, and Sudhir refused. After much cajoling and promises, Daddy threatened to leave Sudhir behind. He would have to walk back home. Sudhir dug his heels in as well. We drove off with a very upset mummy. Daddy said, Sudhir knew the way back home and would walk the three miles.

At home, Mummy and I were on pins and needles. I was hanging off the balcony, trying to spot him. An hour later, I saw Sudhir slowly approaching the house. He was in no hurry, busy kicking a rock along. I ran towards him. He grinned victoriously. I walked all the way from India Gate home, he yelled. I hugged the dusty, sun-kissed visage, rosy cheeks and all. Mummy had a pitcher of ice-cold milk ready, sweetened with a JB Rose soda–a special treat. We both drank with great relish. With a smile, Daddy asked Sudhir, how was the walk? Sudhir gave a straightforward response of not too bad, as he safely crossed major streets using supervised crosswalks. Daddy nodded his approval. No one mentioned anything about boating.

On another occasion, our cousin, Shashi Didi, was home from medical school and had to buy some items for her dorm. Daddy asked her to take Sudhir and me to buy some sturdy school bags. Since Sudhir and I were still young, Shashi Didi took charge. We went shopping but didn’t find any bags we liked. It was getting late, so Shashi Didi returned home. A disappointed Sudhir threw a tantrum right there on the sidewalk. Shashi Didi tried to reason with him gently, but he punched her. She was in tears. A few passers-by grabbed Sudhir, shook him, and scolded him for misbehaving. At home, Shashi Didi walked straight to Daddy and dissolved into tears. A concerned father asked what had occurred. I described Sudhir’s behavior. Daddy apologized to Shashi Didi and asked her not to be too upset.

I reminded Daddy of these two incidents, and he shook his head. He recalled a few of my wild outbursts over the years. This sickness typically affects individuals in their twenties, but our understanding of it is limited.

Juji was planning a small vacation at the end of summer. Along with Mummy, Juji, Fred, and Tara were driving down to Chintaquiti, a little seaside resort in Virginia. Munna, Vinita, and Nalin would join them later. Juji had made phone calls regarding dispersing Sudhir’s ashes in the ocean. Mummy described it to me later:

On this day, the early morning walk along the beach was farther than usual, away from the few other early morning walkers and secluded beach homes. It was quiet, the sun ready to emerge from the ocean, a cool breeze blowing in. Sounds of soft plopping footsteps in the sand and the breaking surf disrupted the morning silence. An occasional screeching gull circled overhead. They came to a long stretch of undisturbed sand, extended ripples to the edge of trees and vegetation. The sun was low near the eastern horizon. White gulls careened overhead in lazy circles and skimmed the waters in graceful swoops. Mummy walked into the ocean, the brine gently lapping at her ankles. She scattered some ashes even as the waves came in and gathered them away. Little by little, she gave Sudhir up to each successive wave in the rising sun’s rays. The ashes garnered in frilly froth swept away into deeper waters. Uday resides by the ocean on the opposite side of the globe. The ashes circled to those shores in some small, significant measure. And Sudhir touched his son at last.