Beloved Brother Gone-Part 1

- Beloved Brother Gone-Part 1

- Beloved Brother Gone-Part 2

In the hushed, soft-lit room, Sudhir lies in a pine coffin draped with a white cloth. Munna, my younger sister, and I arrange white gladiolas on either end with peace lilies along the length. Deep red roses lie in the middle. Mummy enters with Juji (my youngest sister). The priest prepares the thali for the rituals. The arrangement includes coconut, incense, kumkum, flowers, and a flickering oil lamp. Fred (Juji’s husband), Nalin (Munna’s son), and John come in. We sit in a circle on the carpet to complete the rituals: rites to bid farewell and Godspeed to the unhappy soul. Vanita (Munna’s daughter) has stayed home to be with baby Tara (Juji’s daughter).

The priest, a young man, unassuming in speech and manners, is dressed in simple Indian garb. He intones each shloka in measured, solemn sounds. Nalin is standing in for Uday, Sudhir’s estranged son. Under the priest’s guidance, Nalin performs each ancient rite decreed in the chant in his sweet sensitive way.

As the chanting of the scripture proceeds, scenes parade through my mind. The first slow awareness of Sudhir’s illness seeps into my consciousness. The utter foreboding and frightfulness are draining. Incidents and events that have unfolded over the previous two decades. These rush in. It took a while to comprehend the boundless depths; the dark caverns Sudhir was so lost in.

I had visited him a couple of months earlier. His friends had not seen him for a couple of days and had alerted the Salvation Army, where he had been rooming. They found him in bed covered with sores; diabetes weakened his legs; and he could not walk. At the hospital, the doctors seriously considered amputation but ultimately decided against it. First, there should be attempts to save his legs and his life. The sores cleared. Several surgeries later, his legs healed, and he had to learn to walk again.

The hospital refused to release him on his cognizance. He needed to be under medical supervision. They would place him in a minimal care facility where a caretaker would supervise his diet and medication. With newer medication, his brain fog would clear, we were assured.

Over the phone, he sounded so happy I was coming. How could I help him? Invite him home for Christmas for a few days, perhaps? It would give him a break, and we could talk and make plans for the future.

The visit to the St. Joseph facility, where Sudhir had been moved to, was a quick ride from Munna’s home. I spotted him waiting for us outside on the steps. He had lost a lot of weight, and his clothes appeared to hang on him. We went upstairs to his room, and he asked about Brian, Jason, and Kelly. All doing well, I responded. I looked around his room. It was sparse; a bed and a desk, simple furnishings, with a window.

Depositing the few items Munna had brought, he asked if we were hungry. I nodded, and he suggested a small eatery close by. We ate quietly. He was pretty hungry. I could barely control my emotions, seeing him in this forlorn-stricken state. To break the silence, I asked him how he spent his days. Job-hunting took up most of his time. He had visited the library several times but had yet to be successful. It did not carry the technical journals he was looking for. He desired independence, to live alone, and to be near the university and its library. “I am wasting here,” he said.

Once the doctors approved his health and strength, Munna and I promised to get him out of there. He had made several attempts on his own, scheduling appointments with other doctors and following up with them on unsteady legs. The surgery on his knees had saved his legs, which were recovering well enough for him to take the stairs one at a time. Slowly getting his feet together on one step before attempting the next. He tried to impress us by swiftly taking a few steps and steadying himself on the rail. “When?” he asked. Our response, “Doctor’s approval is a must,” was met with silence. We added, “When the medication runs its course.” He looked away quietly, resigned.

Sudhir needed to buy a few things. The next afternoon, we stopped at the Giant Tiger. He looked for sandals, a special kind, he explained. Hearing that, I went in search of an assistant. Sudhir stopped a passing clerk and explained to her what he wanted. His words were slow, concise, and precise, describing what he had seen elsewhere but could not spot in the store. The clerk fetched a pair for him, the right size and color. I picked up some shampoo for Sudhir.

His beard and hair had felt a little coarse from using a harsh bar of soap. On the way out, Sudhir spotted a rackful of telephone handsets. Excitedly, he picked up one. He knew the method of rigging a phone outside his room. He would not have to waste time slowly walking down the stairs when we called him. I told him you don’t need it–we cannot rig it in that place. Yes, I can. I know how to do it, he said. There was a suppressed excitement in his voice, a pleading, insistent tone.

The next day, he called me. He had rigged up the phone. It sat on the floor outside his room. Dial-tone had been activated. He held it to my ear to make sure I heard it. His room and closet were tidy, with no indication of his activities.

Sudhir visited us the next day. He sat on the deck, soaking in the warm spring sunshine. I tried to open up, share thoughts, and make new plans. I wanted to ask him to help Munna, as she and Vinni were on rocky ground. With his proven record, he could talk to her and offer assistance. His support could ease the pain and hurt she was going through. He was familiar with that pain, having lived with it for so long himself. I wanted to talk to him about Christmas–we would gather as a family. He would be healthier and more robust by then, and we could discuss the future.

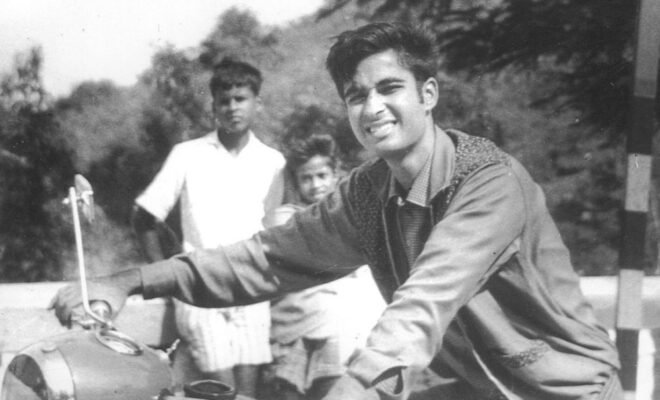

Sudhir dragged on his cigarette, and talked about Jason, Kelly, and Brian again and asked how they were. All are doing fine; they are married and settled down. Sudhir was saddened to learn that Mildred had passed away a few years ago. He talked of Mildred with a faraway look in his soft brown eyes. How much he admired her and what a fun person she was-tender, loving words. I watched him closely, listened to his words. The clarity of his reflections and memories struck me.

I felt he was on the road to recovery! Sudhir continued describing when he had first met Mildred, at John’s and my wedding. No, much earlier, in 1965. My heart sank, and my hands gripped the chair. No, Sudhir, you did not meet Mildred in 1965. You were in college then, planning to graduate and pursue higher studies in Canada.

You met Mildred years later at our wedding, and a few times after. He gave me a gentle reproof. No, you don’t know. I met her first in 1965, unaware of her identity at that time. I gave up. How could I talk about him helping Munna? My words may have a very different connotation for him. He was not ready to join the real world. I said nothing about Christmas either.

I asked him if he remembered his son, Uday. He would be in his mid-teens now. He shook his head. Softly, he said, “If I had a son, he would be here with me now.” I was silent, and he looked up at me, a severe expression and a frown. “Where is this son everyone mentions?” he whispered. “I have no son.” The anger, bitterness, and utter sadness were heartbreaking. I nodded and said, “Don’t give up–he will come.” No, he never did. Years later, when I spoke with Uday, his words were, “Ignorance is bliss.” At some level, Uday understood the depth of his father’s pain and felt helpless facing it, or acknowledging it.

That evening, we were headed to Vinni’s friends’ place. Munna and I fixed a fruit salad in the kitchen, with John at the table reading the newspaper. Sudhir was still outside on the deck, flat on his back, sunning and smoking. I stepped out to continue our chit-chat and pointed to the reclining chair which would be more comfortable. Sudhir lay there and smiled up at me like it’s okay.

I returned inside to finish fixing the fruit salad. Amid brainstorming strategies to make Sudhir more forthcoming, John’s sudden exclamation interrupts my thoughts. Sudhir was taking off all his clothes outside. Rushing out to him, I thought he must be hot on this warm spring day. He was wearing a shirt and sweater with long pants. I brought out a light cover and tucked it over his legs. The scars on his knees still needed shielding.

Gently, I gathered the cover around his chest and waist. I looked closely at his back, his arms, his shoulders, and his legs. There were no open sores anywhere, only scars of the old diabetic sores. Even the back of his legs looked clear. Thin, slender torso and legs; almost child-like, meager, emaciated. Still, not the way Mummy had seen him in the hospital a couple of months prior: gaunt, mere skin and bones. Mummy sobbed and said she could not bear to see him that way.

He napped in the sun’s warmth for quite a while. When he woke up, he was hungry, so he came in and looked in the fridge. He asked if he could have a leftover piece of barbecued steak. I warmed it and served it with A-1 sauce. Sitting at the table, he ate slowly. Wielding a fork and knife, he cut it into neat little pieces. I poured the leftover juices from the fruit salad into a tall glass, placed it in front of him, and demanded he finish it.

Lifting the glass to his lips, a look of surprise brightened his face. The eyes lit up at the sweet, tart taste. “This is good,” he said with a broad smile. That smile! In an instant, we returned to Bangalore. Standing in Mummy’s kitchen, sampling the fancy delights she was forever fixing. For a moment, he was like long ago—a handsome young man full of life and vigor, savoring his family’s togetherness.

The priest’s chanting quickened and broke into my thoughts. He asked us to perform a key ritual to ensure safe passage from here to the next world. Confused, we had worked too hard to keep him in this world. But we had tried to convince Sudhir to stay at the facility a little longer. “You need to regain your strength and complete medication for it to be effective.” He did not respond and continued to put his things away.

Juji called me from Baltimore. I shared my interactions with Sudhir. “He seemed to agree, seemed at peace with himself. He has accepted things as they are, and is agreeable to be patient a little longer.”

Sudhir had no cash on hand. The facility made sure of that. I gave him some US currency but he wanted Canadian bills to save himself a trip to the bank. I had none. He appeared knowledgeable, capable, and self-sufficient at that time. Just a bit longer. Then we will help you get established on your own.