Strange Medicine: Hospital Hauntings

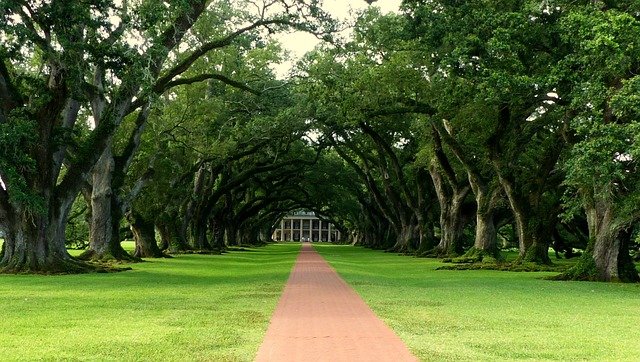

Welcome to Strange Medicine—a series of nonfiction articles based on recent journal-published, peer-reviewed case studies, review articles, meta-studies, scientific studies, and primary literature. Each relates to events that made the medical community’s eyes widen and scratch their heads, though, please note that all are significant toward scientific and medical progress because they also forced us to consider the unknown. This week’s featured image by Dana Stevens on Unsplash (Previous article: Ketamine vs. Depression)

Every year a surprising source of stress in the medical industry comes from a rather spooky source: ghosts. It’s not that researchers believe in ghosts, but the perception and belief in ghosts by patients and medical staff heavily affects acute and continuing care internationally. It turns out many people are afraid of ghosts. While currently understudied, there’s been a recent push to acknowledge the experiences of patients and medical staff as valid, though the phenomena themselves lack conclusive measurability. Given the cost burden of these specters’ appearances, particularly in a post-colonial world, researching how to handle ghosts and what the nature of hauntings actually is, as opposed to denying their existence, maybe the best way forward. This time on Strange Medicine, let’s explore hauntings as a recognized and growing public health concern.

Defining a ghost and how a patient or staff member can be haunted is difficult. Researchers found that individual “ghosts” or events acted as intermediaries for information silenced between generations but passed down. Over time, a body of evidence is built to suggest that hauntings represent collective memories or events that come to the present through shared knowledge, often communicated minimally verbally. These hauntings affect the biomedical field substantially, particularly in areas with a powerful belief in the supernatural. According to an article published last year in The Conversation, as of 2020, between 30 and 50 percent of citizens in the United States and the United Kingdom believe in ghosts. Based on the previously cited anthropological study, these beliefs often lead to the avoidance of places associated with death, such as hospitals and emergency treatment centers. This often leads to worse outcomes for patients. It turns out; people are afraid of ghosts.

Another study based in China found cultural superstitions played a role in whether migrant workers sought medical treatment and how they discussed the politics around the situation. The local belief in ghosts grew after factories in Shenzhen began closing in 2007, and discussion about the ghosts in local culture increased. The author of the study suggested that, given the state of China’s “moral economy,” the use of superstition and ghosts in language and behavioral practices allows for the discussion and expression of displeasure around topics that are otherwise contentious to share in an authoritarian state. This shows the important role that cultural circumstances provide when considering where hauntings may present a problem in the medical system.

Handling the burden of hauntings on public health becomes an especially difficult consideration as some countries move toward offering medical assistance in palliative care that goes beyond providing comfort.

Last year, an Ontario hospital published a study on their need for ghostly intervention. Starting in 2017, the hospital opened a room for Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD). Shortly after, medical staff began reporting sounds without origin, drafts, a general sense of unease, and temperature and lighting changes in the room. The staff began avoiding the room. The hospital offered spiritual support through its Spiritual Health Therapy program to address the haunting experiences of medical staff that impact the experiences of patients in palliative care-seeking MAiD. The hospital formed an interdisciplinary, interdepartmental team between the Ethics, Spiritual Health Therapy, and the Health Equity & Inclusion teams in an effort to find a solution to this growing problem. The “novel” approach they took was to acknowledge the experiences of their staff as valid and approach the care of the room in such as way that acknowledges the beliefs of their staff members.

The team took staff aside and encouraged staff to share their experiences with the room openly. These common experiences primarily included hearing loud sounds (“similar to an individual falling out of their bed”). Other common experiences included “hearing whispering” or “feeling someone touching their arm.” Even staff members that claimed to not believe in the paranormal reported mechanical equipment malfunction, fearful responses to the room, and involuntary muscular responses while in the room. Thirty-five staff members in total took part in this study.

While the spiritual beliefs of staff varied, the experiences of staff remained fairly consistent upon interviewing. Initially, staff requested the MAiD room be moved to a unique part of the hospital entirely. With the help of staff, the team developed a procedure with Spiritual Health Therapy to treat the space and improve the experience for staff members. The requested procedures performed included daily room blessings, reading scripture aloud in the room, herbal smudging, and more focused help by Spiritual Health Therapy for individual staff members.

As of the publication in November 2020, this interdisciplinary approach that acknowledged the cultural diversity of staff provided a potential approach usable in future research on addressing the mounting costs of handling the aftermath of death. Given that death is unavoidable in hospitals and the data on how MAiD is impacting Canada’s health system is still emerging, this study provides a path forward for future quantitative pilot studies on reducing the cost burden of haunting experiences in hospitals.

As this field of human behavioral research continues to grow, it is likely that we will see more money spent on studying how it impacts various aspects of human life, including our health and ability to seek health care. Remember, less than a hundred years ago, taking the time to listen to our hospital staff and patients in order to solve problems was unheard of beyond Florence Nightingale’s efforts in medical reform. Keep an eye on this fascinating growing body of research. Perhaps we can use the study of hauntings to acknowledge and change our behavior to create a better future for everyone using hospital systems.